Congress has to take the sustainability of the federal government’s finances seriously. The only way to address the fiscal perilous path we’re on is to identify and advance bipartisan solutions.

The Big Picture

Although Elon Musk rode into Washington on a promise to cut $2 trillion of federal spending, the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) claims to have cut only $175 billion, or less than 9 percent of the total goal. This isn’t a surprise. Musk walked about his promise of $2 trillion worth of spending cuts before Trump took office. Musk also damaged his credibility by making wild, misleading, and false claims about federal spending. As Musk continued his work, he became an easy target, and his popularity waned.

The cuts that DOGE claims likely don’t even add up to the $175 billion boasted on its so-called “wall of receipts.” Add to that the White House is sending a rescissions package to cut only $9.4 billion in budget authority to Congress. This rescissions package supposedly represents only some of the DOGE cuts.

The good news is that the past several months have put a renewed focus on federal spending, but it’s deeper than the so-called “woke spending” that grabs headlines on popular conservative media outlets. It’s also more extensive than simply raising taxes on higher-income earners, as progressives would have us believe. The bad news is that federal spending continues to rise.

Zooming In

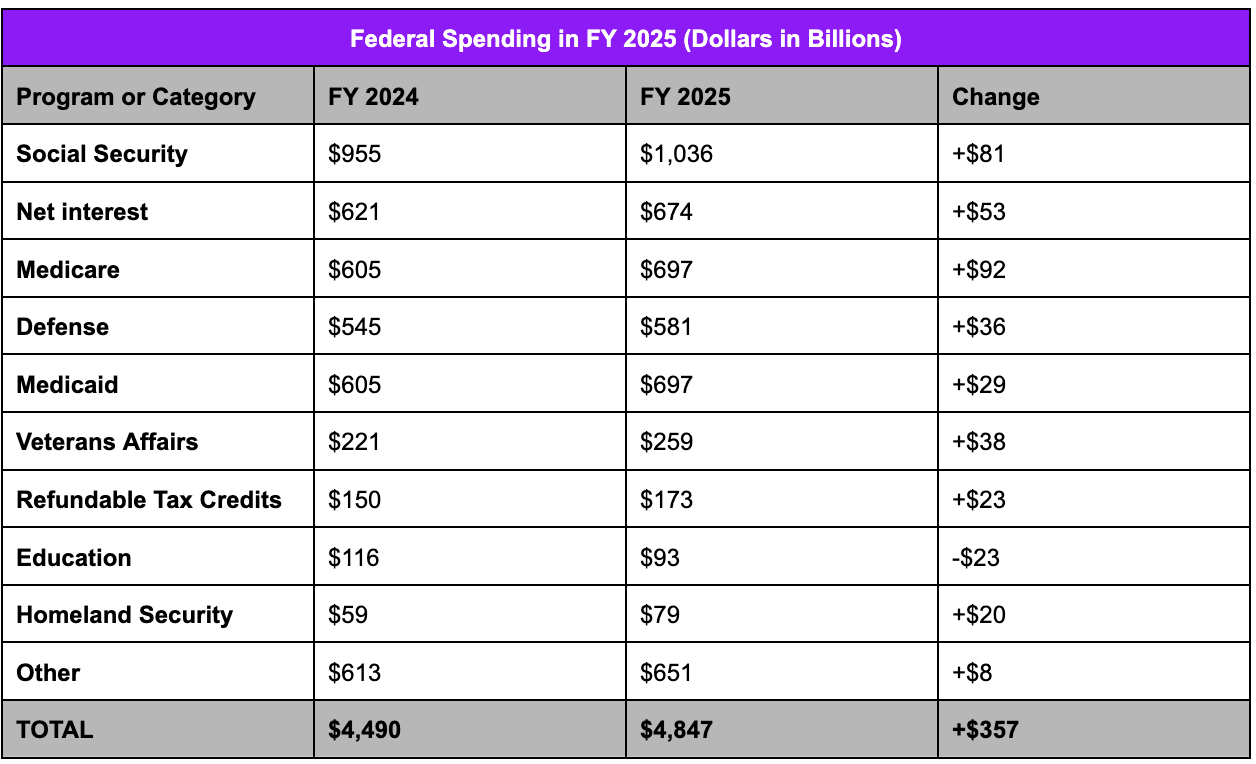

Let’s look at the most recent Monthly Budget Review published by the Congressional Budget Office. The data show that the budget deficit through the first eight months of FY 2025 (October 2024 through May 2025) is nearly $1.4 trillion. That’s $160 billion higher than the same period in FY 2024. Although tax receipts are up 6%, outlays have increased by 8%. In other words, the federal government has spent $357 billion more than it did at the same point in FY 2024.

We Are So Incredibly Screwed

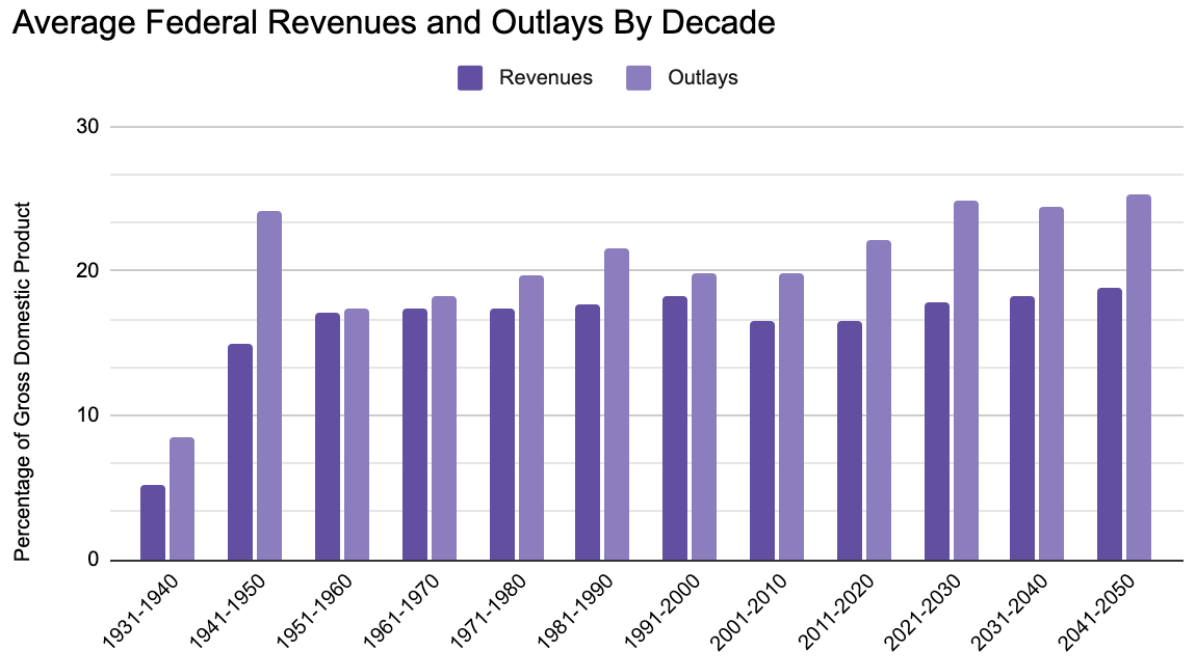

We have our weekly staff meetings at the Independent Center on Monday. It’s not out of the ordinary to hear me say, “Things are going great,” with a heaping dollop of sarcasm when I talk about deficits and the national debt. I frequently review the numbers, and the fiscal crisis on our doorstep is readily apparent. It’s simple math. The government of the United States is projected to spend more than it receives in tax revenue. By a lot.

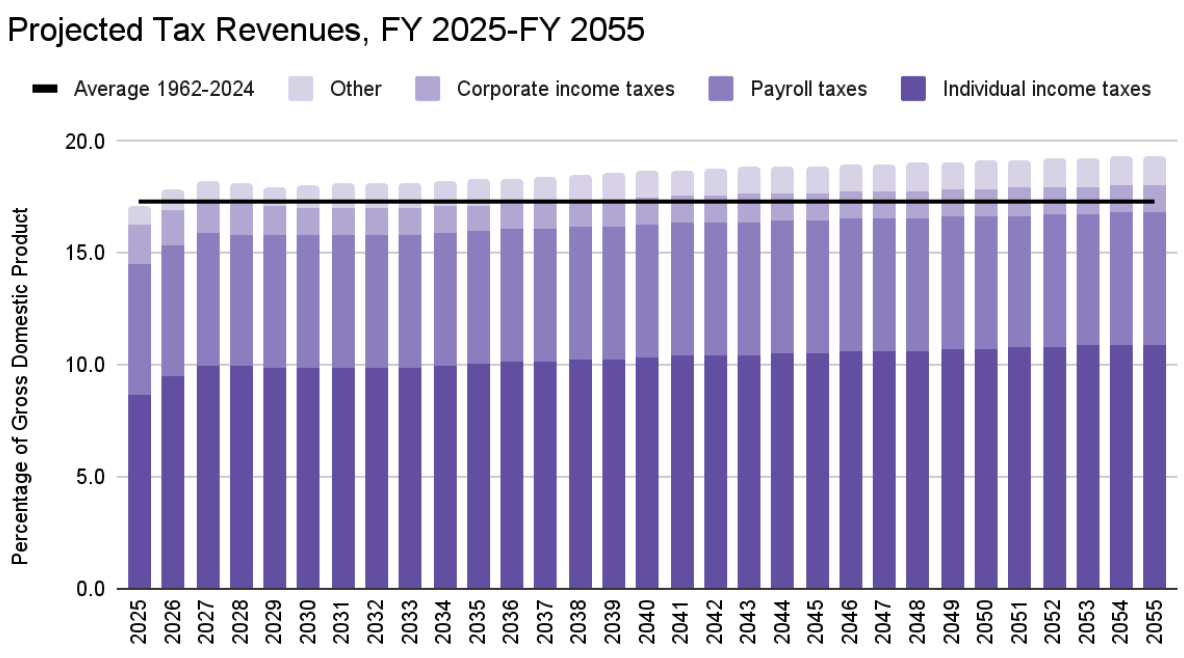

The data used for the calculations come from the long-term budget projections published by the CBO. These data were released in March 2025. We use historical data published by the CBO in January 2025 for comparisons. It’s important to note that these data are based on current law. For example, under current law, the individual tax cuts enacted under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 are scheduled to expire at the end of 2025. The CBO assumes those tax cuts will expire as scheduled. Thus, the effects of the so-called “One Big Beautiful Bill Act,” H.R. 1, aren’t taken into consideration.

Why include historical tax revenue? Well, it’s important to provide context. Tax revenues are expected to be higher as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) from FY 2026 through FY 2055 than the historical average from FY 1962 through FY 2024. I know there’s a belief among some that the 90-plus percent tax rates that were the norm in the ‘50s somehow mean we’d have significantly more tax revenue. The Office of Management and Budget indicates that tax revenues averaged 17.1 percent in the 1950s, but the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s saw slightly higher average revenues. Of course, the 1980s and 1990s were periods of lower marginal tax rates compared to the previous decades.

In and of itself, a deficit isn’t inherently a problem, provided it’s manageable. The reason the deficit is a problem for the United States is that the federal government has a structural deficit. However, the deficits that the United States has seen over the past several years, as well as the deficits it’s projected to see over the next several years, create an extreme risk that could send shockwaves throughout the rest of the country.

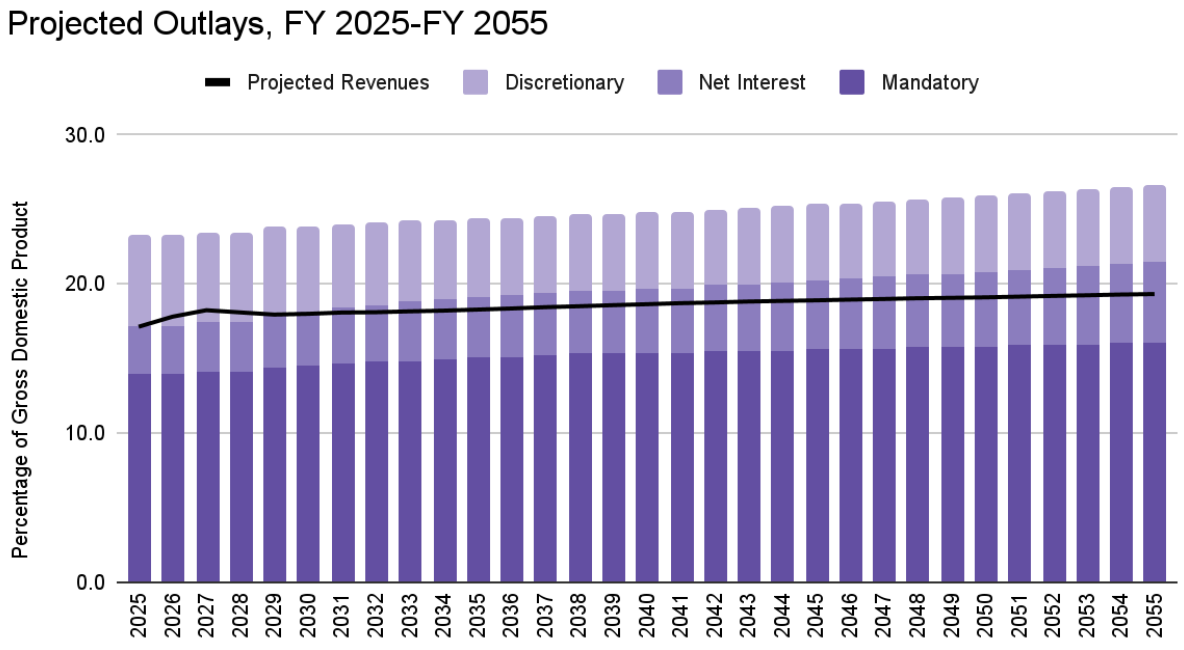

As you can see from the chart immediately above, the growth of mandatory spending and net interest on the share of the debt held by the public are the drivers of federal spending. Even more concerning is that this chart doesn’t tell the story because it’s based on current law and doesn’t take congressional behavior into account. However, the CBO recently published a different outlook that considers various factors that could substantially worsen deficits and debt. One of those factors is the cost of debt service.

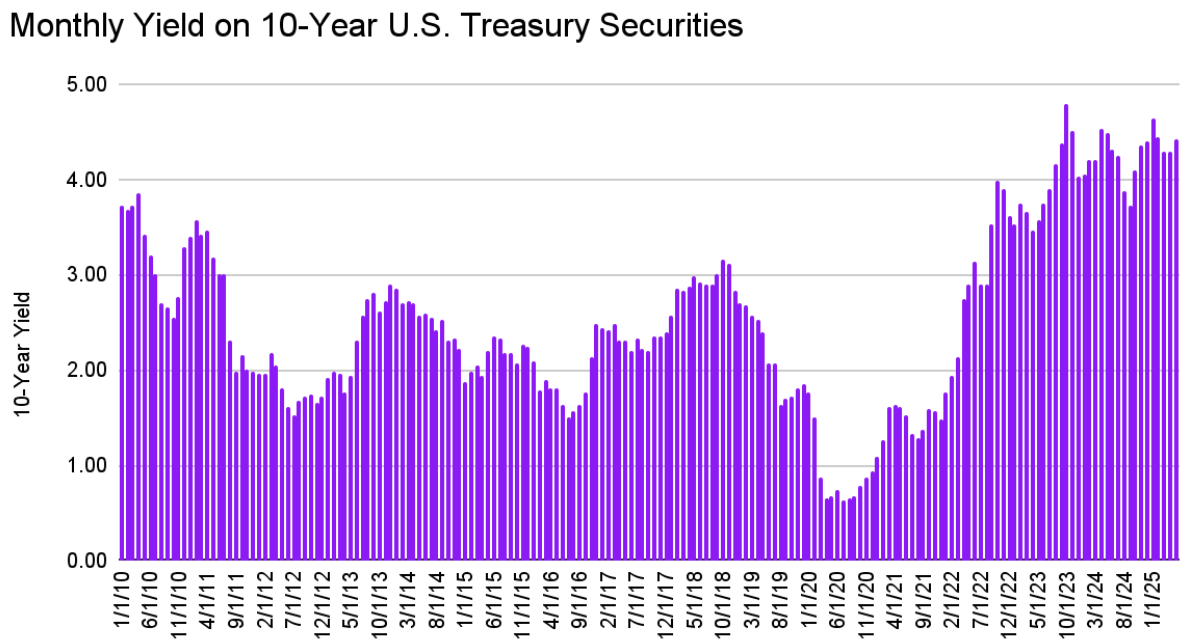

When the federal government runs a deficit, it has to sell securities on the market. Domestic and foreign investors, banks, pension funds, and the Federal Reserve purchase those securities. The purchaser is guaranteed a percentage return, also known as a yield. In January, the CBO projected that the yield on 10-year Treasury securities would be 4.20% in Q4 2024, 4.25% in Q1 2025, and 4.11% in Q2 2025. The yield on 10-year Treasury notes was 4.28% in Q4 2024 and 4.45% in Q1 2025. As of June 23, the yield was 4.34%; however, it fluctuates daily.

The 10-year Treasury yield is the benchmark for the economy. There are impacts across the economy when the yield rises. Not only does a higher yield mean increased borrowing costs for the federal government, but it also affects private borrowing for homes, vehicles, credit cards, and more. The problem with the CBO’s projections for interest rates is that the federal government is spending more on net interest. Since FY 2024, outlays for net interest have surpassed defense discretionary spending. We’re borrowing more and more every year, primarily due to increased spending on Medicare and Medicaid. If Social Security and Medicare aren’t modernized, borrowing will rise dramatically over the next decade.

Social Security and Medicare Are Running Out of Money

Two of the primary drivers of long-term budget deficits and debt are Social Security and Medicare. The third primary driver is interest on the share of the debt held by the public. Social Security and Medicare Part A (Hospital Insurance) are funded through taxes collected by the federal government. That tax revenue is collected and placed into the trust funds for those programs.

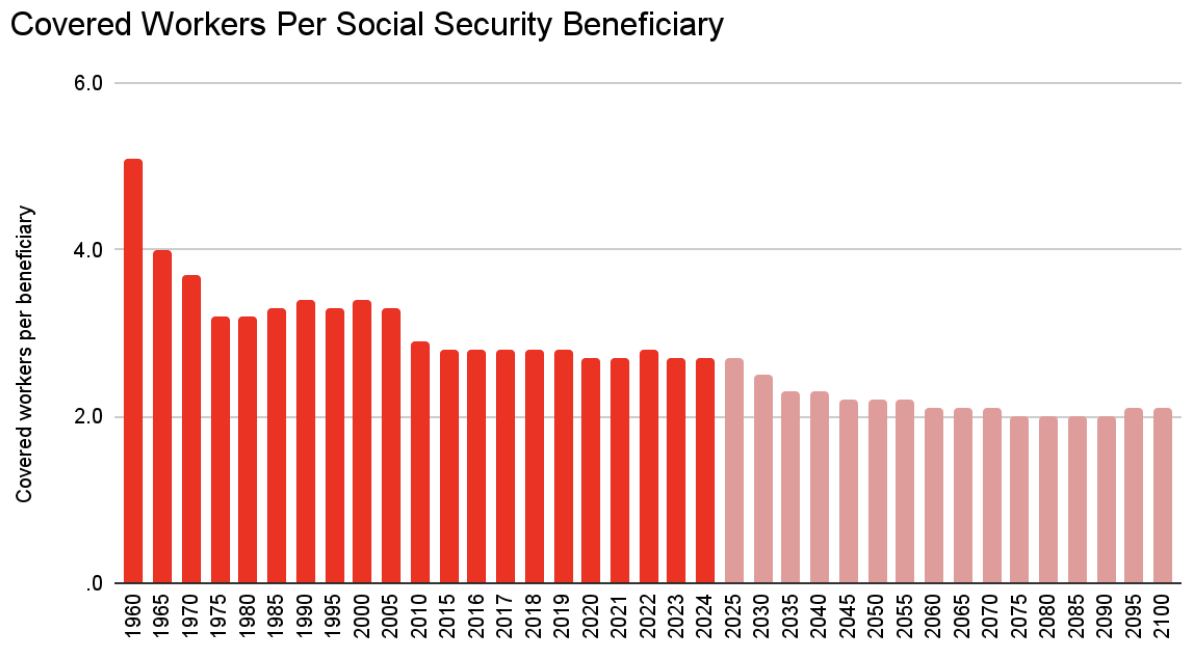

In June, the trustees for Social Security and Medicare separately released reports updating the public on the perilous position of the programs. Due to the increasing number of retirees and a workforce that’s gradually declining, the trust funds are approaching insolvency. In 1945, there were roughly 42 covered workers per beneficiary. By 1955, that figure declined to 8.6. Currently, there are 2.3 covered workers per beneficiary. (In the chart below, projected data are in light red.)

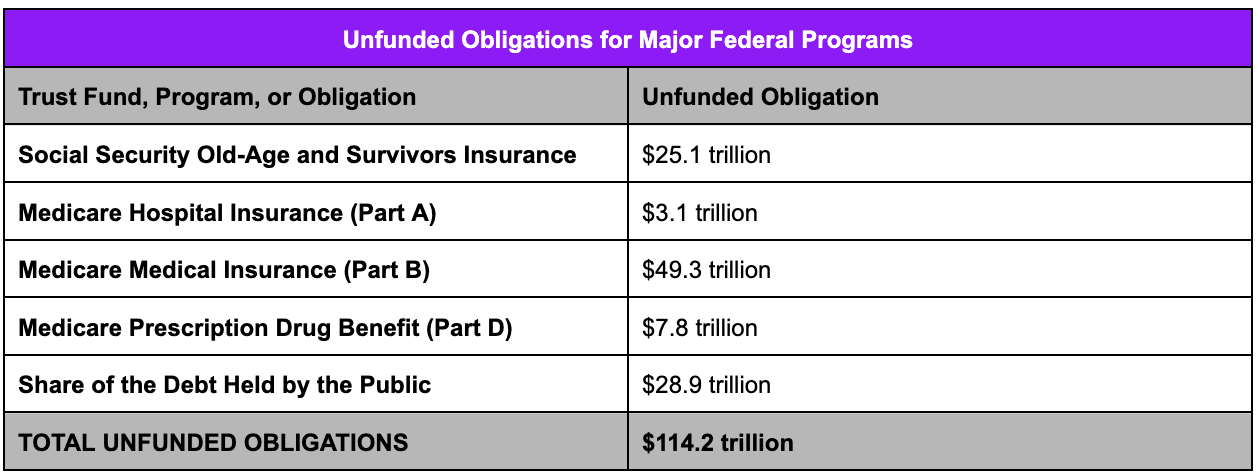

Although the Social Security Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund had total reserves of $2.54 trillion as of the end of December 2024, the increasing number of people reaching retirement age will diminish those reserves. The trustees' report projects that the OASI Trust Fund will be depleted in 2033. (Including the Disability Insurance Trust Fund, depletion will occur in 2034.) The good news is that this is the same projected depletion year as the previous trustees’ report. The bad news is that the combined unfunded obligations for the two trust funds amount to $25.1 trillion.

If Congress doesn’t take action, either to modernize the program or to bail out the trust funds, the OASI Trust Fund would be able to pay out only 77% of scheduled benefits. To make the trust fund solvent, the trustees’ report explains, “revenue would have to increase by an amount equivalent to an immediate and permanent payroll tax rate increase of 3.65 percentage points to 16.05 percent beginning in January 2025.” Of course, as the report notes, reductions in benefits for current and/or future beneficiaries, or a combination of tax increases and benefit reductions, could be options.

The only part of Medicare that’s funded through the payroll tax and the additional Medicare tax created by the Affordable Care Act is Medicare Part A, or Hospital Insurance. Medicare Parts B (Medical Insurance) and D (Prescription Drugs) are financed through transfers from general tax revenue and premium payments. Medicare Part C (Medicare Advantage) is financed through payments from Part A and Part B.

There are two Medicare trust funds–the Hospital Insurance (HI) Trust Fund and the Supplemental Medical Insurance (SMI) Trust Fund. The HI Trust Fund will be depleted in 2033–three years earlier than estimated in last year’s report. The change is attributed to higher outlays in 2024 for Part A and higher projected outlays in future years. Unless Congress takes action, the HI Trust Fund will be able to pay out 89% of scheduled benefits.

The total unfunded obligation for HI is $3.1 trillion. Because Medicare Parts B and D don’t have dedicated revenue sources, the unfunded obligations for these programs are $49.3 trillion and $7.8 trillion. Add in the unfunded obligation for OASI and the public's share of the debt—$28.9 trillion, as of June 20 (this figure excludes intragovernmental debt)—and the total unfunded obligations for the federal government are $114.2 trillion. The table below details the unfunded obligations.

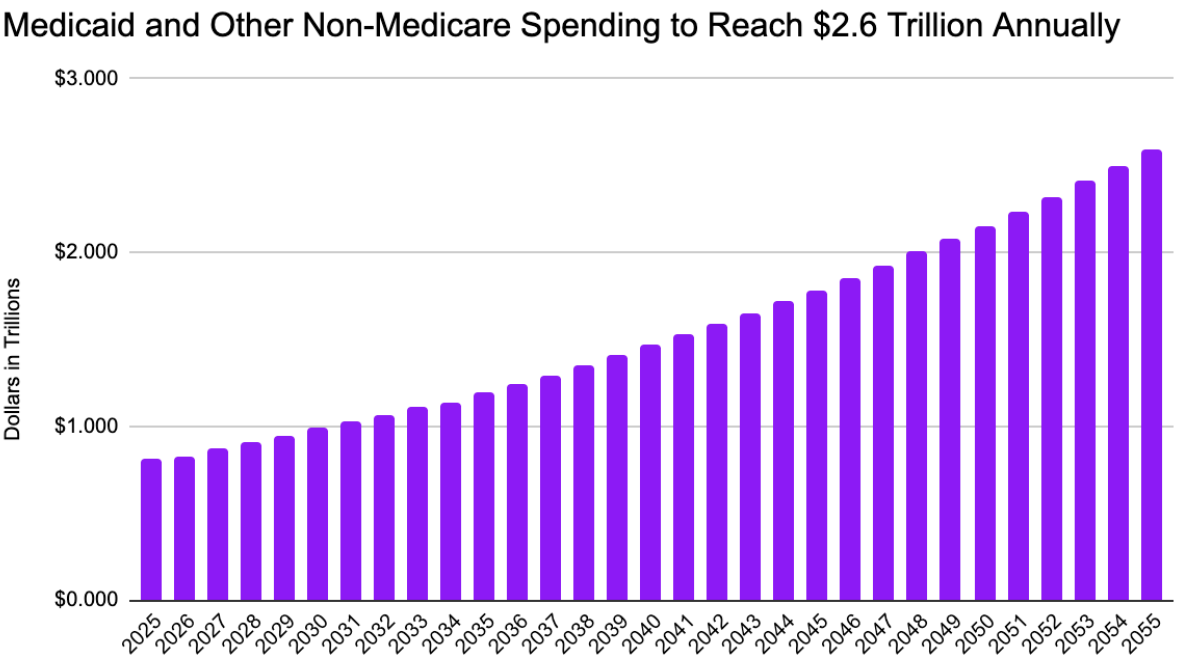

The doesn’t include other trust funds with unfunded obligations, nor does it include Medicaid spending. However, the CBO projects spending for Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), premium tax credits under the Affordable Care Act, and other non-Medicare spending is projected to be just over $48 trillion from FY 2025 through FY 2055.

As a result of the federal government not managing the nation’s finances responsibly, the share of the debt held by the public is expected to rise dramatically over the next few decades. Depending on how sensitive private investment is to deficits, if interest rates were higher, if we experience slower-than-projected economic growth, or if revenues and discretionary outlays remain at the historical average, debt as a percentage of GDP could be significantly higher, exceeding 200% in some alternative scenarios.

Independent Lens: We Need a Fiscal Commission

Congress has to take the sustainability of the federal government’s finances seriously. The only way to address the fiscal perilous path we’re on is to identify and advance bipartisan solutions. Although nearly everyone agrees that individuals who currently receive Social Security and Medicare, or will be on the programs in the next five years or so, should continue to receive the same benefits, the programs must change for those who aren’t on them. It may mean other tough choices.

Although there isn’t a bipartisan solution for these programs yet, there is bipartisan legislation to put us on the path to those solutions. Reps. Bill Huizenga (R-MI) and Scott Peters (D-CA) have introduced the Fiscal Commission Act, H.R. 3289. This bill would create a 16-member commission to explore changes to existing law to modernize federal programs and other avenues to address the budget deficit. Should the commission make recommendations, those recommendations, in legislative text, will receive expedited consideration in the House and the Senate.

.jpg)